Sockets in C

Posted by Alejandro Diaz on June 16, 2021A high-level introduction to sockets, or what I’ve been reading for the past week.

Introduction

When computer networks (the prelude to the internet) were conceived, it was up to programmers at the time to create an architecture that was reliable and future-proof. Sockets came about as a middle layer between the metal of the machine and software applications.

The nice thing about this layer is that it lends to abstracting away details. Abstracting the hardware and software layer means that these layers of independent of one another. That is, software applications are unaffected by hardware architecture and vice versa. In fact, we’ve seen this happen many times already with the transition from dial-up to broadband (and from Netscape to Chrome). The convenience of the abstraction allows programmers to not worry about the underlying hardware. So, what exactly is a socket? And why are they important?

This article will aim to give a brief overview. I leave it up to the reader to chase more information about what they find interesting, but this article summarizes what I have learned from multiple sources (cited at the bottom).

Sockets

Sockets have changed remarkably little since their inception. Conceptually, you can think of them as akin to file buffers! The socket follows the UNIX ideology that everything is a file. The socket allows one to read, write, and send off data to the machine’s hardware. The socket’s API was designed to be expanded to have many, many protocols, but all you need to know about is two socket families and two IP protocols.

- User-Datagram Protocol (UDP)

- UDP sockets do not guarantee data delivery. It is a best-effort protocol

- The best-effort method provides faster sends and requires less information than its counterpart

- UDP is commonly used for gaming and other applications that can afford packet-loss

- Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)

- TCP guarantees that the data is sent to the receiver sequentially and error-free

- TCP is slower but handles any critical data transmissions where both sides need to be sure that the data has been sent and received

- This socket type is extremely common

Sockets essentially ‘bind’ to an address on your local computer that corresponds to the hardware. There can only be one socket per address reserved, and the operating system tends to reserve ports below 1024. Once bound, you can write and read to and from that address. It’s important to remember that neither TCP nor UDP sockets can guarantee that the data can be sent/read in one cycle. Be conscious of buffer limitations, especially from a C/C++ perspective where keeping track of memory is essential.

IP versions complicate sockets

Life was once simple, there were IP addresses to go around. We all used IPv4 without a second thought. Unfortunately, these addresses (you’ve seen them, something like 192.168.1.0) need to be unique to be used on the web. We’ve run low.

To future proof the web, the big wigs that set standards came out with IPv6 (something like 2001:0db8:0000:0000:0000:8a2e:0370:7334). IPv6 gives many, many more addresses. The two IP addresses don’t mix out of the box. That said IPv6 does provide interoperability. You still need to be wary of making client/server applications that can handle both IP standards. Let’s discuss that now.

The Basic Pattern of networking

There are two classes of applications on the web. There is the client and the server. A server application waits for a client to connect to an address that the application is bound to. Upon a client connection, the server application will use an additional socket (so that the original can keep watch for new clients), and on the new socket serves the client with data or wait for a command.

A client will bind to a socket on its machine, then take an address or name and attempt to connect to the address.

Both the server and client applications can send, write, and receive. There is a difference, however. A user controls the client program and typically sends commands to the server. A server runs forever and reacts to given commands. This basic pattern repeats itself on the internet. Anything from Spotify to your bank website follows this pattern.

We are going to replicate the pattern here with a simple program. The program will be IP agnostic, with the caveat that we will have to explain quite a few concepts, but the payoff is you can copy this style and get rolling (if traffic isn’t insane). Without further ado:

Client code

This code example implements a TCP client, composed of four steps:

- Create a TCP socket using socket()

- Establish a connection to the server using connect()

- communicate using send() and recv()

- close the connection using close()

The client takes a server address/ domain name, a string, and, optionally, a port. This example borrows heavily from (Donahoo, Calvert, 2009).

includes

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <netdb.h>

main

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

// we want 4 args the program name and the last 1 is optional

if (argc < 3 || argc > 4){

fputs("Parameter(s): <Server Address/Name> <Echo String> [<Server Port/Service>]", stderr);

exit(-1);

}

char *server = argv[1]; // first argument, after the program name, is the server address/name

char *echoString = argv[2]; // second arg: string to echo

// third argument is optional server/port number

char *service = (argc == 4) ? argv[3] : "echo";

int sock = setupTcpClientSocket(server, service);

if (sock < 0) {

fputs("setupTcpClientSocket() failed: unable to connected", stderr);

exit(1);

}

size_t echoStringLen = strlen(echoString);

ssize_t numBytes = send(sock, echoString, echoStringLen, 0);

if (numBytes < 0) {

fputs("send() failed", stderr);

exit(1);

}

else if (numBytes != echoStringLen) {

fputs("send() sent an unexpected number of bytes", stderr);

exit(1);

}

// receive the same string from the server

unsigned int totalBytesRecvd = 0;

fputs("Received: ", stdout);

while (totalBytesRecvd < echoStringLen) {

char buffer[256];

numBytes = recv(sock, buffer, 256-1, 0); // receive up to the buffer size - 1 for the \0 character

if (numBytes < 0) {

fputs("recv() failed", stderr);

exit(1);

}

else if (numBytes == 0) {

fputs("recv() connection closed prematurely", stderr);

exit(1);

}

totalBytesRecvd += numBytes;

buffer[numBytes] = '\0';

fputs(buffer, stdout);

}

fputc('\n', stdout);

}

setupTcpClientSocket

int setupTcpClientSocket(const char *host, const char *service)

{

struct addrinfo addrCriteria; // addrCriteria used to filter on available addresses

memset(&addrCriteria, 0, sizeof(addrCriteria));

addrCriteria.ai_family = AF_UNSPEC; // dont care if ipv4 or ipv6

addrCriteria.ai_socktype = SOCK_STREAM; // want a TCP

addrCriteria.ai_protocol = IPPROTO_TCP; // again, tcp protocol

struct addrinfo *servAddr; // will hold the returned linked list of addresses

int rtnVal = getaddrinfo(host, service, &addrCriteria, &servAddr); // getaddrinfo is your friend! very important function

if (rtnVal != 0) {

fputs("getaddrinfo() failed", stderr);

exit(1);

}

int sock = -1; // default a sock as negative, so we know if it does not bind

for (struct addrinfo *addr = servAddr; addr != NULL; addr = addr->ai_next) {

sock = socket(addr->ai_family, addr->ai_socktype, addr->ai_protocol); // try to bind for each addr in linked-list until successful

if (sock < 0)

continue;

if (connect(sock, addr->ai_addr, addr->ai_addrlen) == 0)

break; // break out of loop if success

close(sock);

sock = -1; // finished loop without a success! bad!

}

freeaddrinfo(servAddr); // remove the linked list from memory since we're finished with it

return sock; // our new socket

}

Server code

The code implements a TCP server, composed of four steps:

- Create a TCP socket using socket()

- Assign a port number to the socket with bind()

- Tell the system to allow for connections to the port using listen()

-

Repeat the following:

a. Call accept() to get a new socket for each client connection

b. communicate with the client with send() and recv

c. close the client connection with close()

The server takes a port as its argument. The code borrows from (Donahoo, Calvert, 2009).

includes

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <arpa/inet.h>

// we will use this to specify the queue of connections to our server

static const int MAXCON = 5;

main

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

if (argc != 2) { // we want two arguments, the program itself and the port

fputs("Parameter(s): <Server Port/ Service", stderr);

exit(1);

}

char *service = argv[1]; // the port we want to serve bind

int servSock = setupTcpServerSocket(service); // let's make our server socket

if (servSock < 0) {

fputs("setupTcpServerSocket() failed", stderr);

exit(1);

}

for (;;) { // run forever

int clntSock = acceptTcpConnection(servSock);

handleTcpClient(clntSock);

close(clntSock);

}

}

setupTcpSocket

int setupTcpServerSocket(const char *service)

{

struct addrinfo addrCriteria; // we use the addrinfo structure to hold the info... addrinfo is flexible

memset(&addrCriteria, 0, sizeof(addrCriteria)); // clear out the struct

addrCriteria.ai_family = AF_UNSPEC; // IP agnostic

addrCriteria.ai_flags = AI_PASSIVE; // any

addrCriteria.ai_socktype = SOCK_STREAM; // stream socket (TCP)

addrCriteria.ai_protocol = IPPROTO_TCP; // TCP protocol

struct addrinfo *servAddr; // this will hold all the returned addresses that match the criteria... linked list style

int rtnVal = getaddrinfo(NULL, service, &addrCriteria, &servAddr); // getaddrinfo is our friend! works with both addresses and names

if (rtnVal != 0)

{

fputs("get addrinfo() failed", stderr);

fputs(gai_strerror(rtnVal), stderr);

exit(1);

}

int servSock = -1;

for (struct addrinfo *addr = servAddr; addr != NULL; addr = addr->ai_next) { // loop through all the returned addresses until one works

servSock = socket(servAddr->ai_family, servAddr->ai_socktype, servAddr->ai_protocol); // try to bind the socket

if (servSock < 0)

continue; // socket creation failed, try the next one

if ((bind(servSock, servAddr->ai_addr, servAddr->ai_addrlen) == 0) && (listen(servSock, MAXCON) == 0)) // if bound works and can listen to socket

{

struct sockaddr_storage localAddr; // sockaddr_storage is IP agnostic

socklen_t addrSize = sizeof(localAddr);

if (getsockname(servSock, (struct sockaddr *) &localAddr, &addrSize) < 0){

fputs("getsockname() failed", stderr);

exit(1);

}

fputs("binding to ", stdout);

printSocketAddress((struct sockaddr *) &localAddr, stdout); // printing what address we bound to

fputc('\n', stdout);

break;

}

close(servSock);

servSock = -1;

}

freeaddrinfo(servAddr);

return servSock;

}

acceptTcpConnection

int acceptTcpConnection(int servSock)

{

struct sockaddr_storage clntAddr; // client address

socklen_t clntAddrLen = sizeof(clntAddr); // need the length of the client's address

// wait for the client to connect

int clntSock = accept(servSock, (struct sockaddr *) &clntAddr, &clntAddrLen); // accept a connection

if (clntSock < 0) // negative return indicates failure

{

fputs("accept() failed", stderr);

exit(-1);

}

fputs("handling client ", stdout);

printSocketAddress((struct sockaddr *) &clntAddr, stdout); // just printing who connected

fputc('\n', stdout); // break line

return clntSock;

}

handleTcpClient

void handleTcpClient (int clntSocket)

{

char buffer[250]; // buffer one byte

// receive message from client

ssize_t numBytesRcvd = recv(clntSocket, buffer, 250, 0); // 256-1 is to make room for '\0'

if (numBytesRcvd < 0){

fputs("recv() failed", stderr);

exit(1);

}

// send received string and receive again until end of stream

while (numBytesRcvd > 0)

{

ssize_t numBytesSent = send(clntSocket, buffer, numBytesRcvd, 0);

if (numBytesSent < 0){

fputs("send() failed", stderr);

exit(1);

}

else if (numBytesSent != numBytesRcvd){

fputs("send() Sent unexpected number of bytes", stderr);

exit(1);

}

// see if there is more data to receive

numBytesRcvd = recv(clntSocket, buffer, 250, 0);

if (numBytesRcvd < 0){

fputs("recv() failed on second iteration", stderr);

exit(1);

}

}

close(clntSocket);

}

printSocketAddress

void printSocketAddress(const struct sockaddr *address, FILE *stream) // this is just a function to print connection

{

if (address == NULL || stream == NULL)

return;

void *numericAddress; // we're not sure of the size yet, so we use void

char addrBuffer[INET6_ADDRSTRLEN]; // INET6_ADDRSTRLEN is the max len of an ipv6 connection, this is enough for both ipv6 and ipv4

in_port_t port;

switch(address->sa_family)

{

// need to convert to given address either to ipv4 or ipv6 compatible structure, using sockaddr_in or sockaddr_in6

case AF_INET:

numericAddress = &((struct sockaddr_in *) address)->sin_addr;

port = ntohs(((struct sockaddr_in *) address)->sin_port); // network to host short

break;

case AF_INET6:

numericAddress = &((struct sockaddr_in6 *) address)->sin6_addr;

port = ntohs(((struct sockaddr_in6 *) address)->sin6_port); // network to host short

break;

default:

fputs("[unknown type]", stream);

return;

}

if (inet_ntop(address->sa_family, numericAddress, addrBuffer, sizeof(addrBuffer)) == NULL) // convert ipv4 or ipv6 address (inet) from bytes (network), to printable (string)

fputs("[invalid address]", stream);

else {

fprintf(stream, "%s", addrBuffer); // print the address

if (port != 0)

fprintf(stream, "%u", port); // print the port

}

}

Running our example

Here is a github link of the files, which we have names client.c and server.c. We need to do the following to make this example run:

- compile the two programs using a compiler like gcc:

gcc client.c -o client&&gcc server.c -o server - run the server first,

./server 5000(running at port 5000)

- run the client on a different terminal window at the server address and port, in this example 0.0.0.0 5000,

./client 0.0.0.0 "echo this" 5000

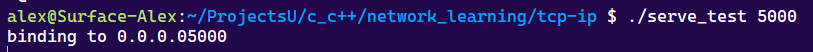

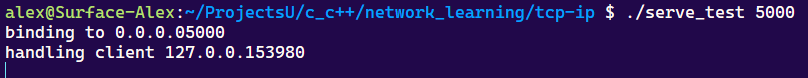

You should see this on the server window

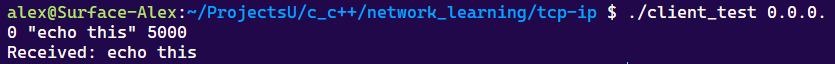

and this and on the client window

and this and on the client window

Where to go from here?

To those interested in learning more about sockets and their rich history in networks, I direct you to the following sources. The first is completely free and a high-level overview in a similar style to this article. The second provides more depth and background and comes from an academic setting.

Bib

- Hall, B. “Beej J. (n.d.). Beej’s Guide to Network Programming: Using Internet Sockets. https://beej.us/guide/bgnet/

- Donahoo, M. J., & Calvert, K. L. (2009). TCP/IP sockets in C: Practical guide for programmers (2nd ed). Morgan Kaufmann. https://www.sciencedirect.com/book/9780123745408/tcp-ip-sockets-in-c

‘Till next time space cowboy

– Alex