An Introduction to Thread Concurrency- a OS Perspective (Part 2)

Posted by Alejandro Diaz on November 01, 2021A readable summary of how an operating system facilitates multi-threading and how it works. This series of articles will cover key questions about how an Operating System works. After you read it, you will walk away knowing what the OS does behind the scenes to make your life easier when creating multi-threaded applications. You won’t need much of any background to read this article, but it will help if you are familiar with a low-level language, like C. If you want to learn more, the end of this article provides my sources and what you can use in your own studies. Make sure to check out part one.

Processing a Process

In part one, we used the terms “process” and “application” interchangeably. This is not entirely correct, as you will see. An application is represented as one or more processes. A process, by definition has its own resources and data, the most basic unit of work on the user level. Recall that the OS uses processes to achieve its goal of modular and isolated programs.

Note, this article will be more in-depth than part 1. If anything looks confusing, feel free to skip it. The important stuff is the conceptual level and why things happen. You can always look up the details!

Processes

At its core, a process represents a state of execution. The OS has to keep track of a process’s state to manage it. Each process has a corresponding Process Control Block (PCB) that the OS can track its state. A PCB has:

- Program counter, a counter held in the CPU that tracks what line of execution the program is on

- A Process ID

- A Virtual address space, the OS will allocate each process with memory, but to the process, this allocation looks like the entire machine’s memory! In reality, the OS has abstracted and decoupled physical memory to virtual memory. The effect is simplified memory management

- A Stack pointer, part of a process’s state is the state of its stack. A stack is simply a place in memory that lets a program track what data it currently is using in its scope

- A Heap, a section of memory that holds dynamically allocated data for the process

- Static data/text, loaded in when the process first launches, does not change throughout the execution

- CPU register state, the state of registers when the process is working, may change throughout the execution

It is important to remember that processes are modular. Each process has ownership of its resources. Recall that one of the operating system’s missions is to guarantee that process isolation and security.

Process Control Block (PCB)

The OS has to track all of this information along with some scheduling information with each process. Operating system engineers came up with the process control block (PCB) to do just that. For example, the program counter is initialized to the first instruction if the process is new. These fields are updated when they change (e.g., program counter pointing to the next line). The operating system is responsible for updating the PCB.

The PCB is used to track the state of execution of any given process. No single process is allowed to dominate the CPU, so the OS must have the ability to save and restore a process as it gets dispatched and preempted to the CPU. The PCB enables this so-called context switch to occur.

Context switches

The operating system takes a hit to performance each time a context switch occurs. Context switches are expensive. First, The OS is obligated to use CPU cycles to store the current processes information into its PCB and load the new processes state from its PCB. Second, a context switch will result in a cold cache (see part 1), slowing down execution.

It is the interest of the operating system to avoid context switching whenever possible.

What do you think are some policies an OS can use to avoid context switching? When would the OS be forced to context switch? Keep context switching in mind as you read the rest of the article.

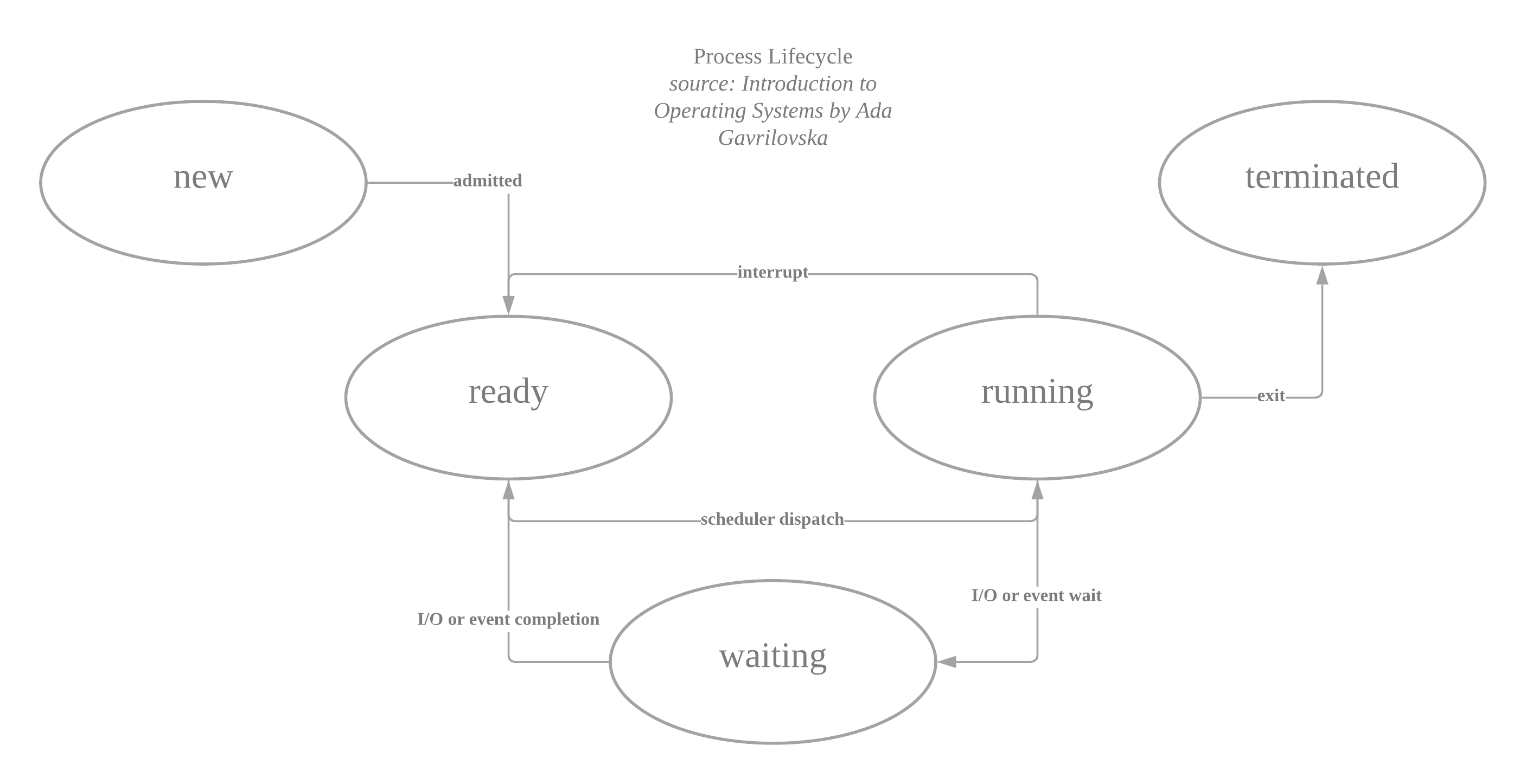

Process lifetime

Each process goes through this life cycle. Let’s discuss what each stage entails:

- new: Process gets created; the OS allocates and creates a process control block for the process and its resources (heap, stack, PCB)

- ready: The scheduler decides to queue the process to the CPU. The scheduler maintains the queue.

- running: The process is running on the CPU. The CPU can only run one thing at a time. On an interrupt, the CPU will no longer run the process. Operations that require I/O access will result (e.g., system call like read()) in the process being moved to waiting. The scheduler decides when to context switch.

- waiting: Processes here are completing some longer event. Usually, this is handled by the peripheral (e.g., the OS will request the data from the hard drive). The scheduler will move the process to ready when the operation completes.

- terminated: A process that completes and exits or one that results in an error code.

What role does the OS scheduler play?

The scheduler is vital for moving processes on and off of the CPU. For this to happen, the OS needs to:

- Preempt: interrupt and save the current context of the executing process

- Schedule: determine what to run next, depending on the operating system’s scheduling policy

- Dispatch: send the chosen process to the CPU and initiate a context switch

Naturally, the next question is how often should the scheduler run? The answer is it depends on the OS’s policies and the state of the process. For example, if the process blocks (i.e., waiting on something to finish like saving to a disk) and it takes less time to context switch than the blocking operation, it may make more sense to go ahead and run the scheduler for a context switch. Note this all affects CPU efficiency, or (total time doing user work)/(total time doing user work + total time doing OS work).

Can processes communicate with each other?

Recall that one of the guiding principles of OS design is the modularity of user processes. Can we keep the modularity of processes while allowing processes to communicate? Engineers designed inter-process communication (IPC) to facilitate processes to communicate. IPC mechanisms do not compromise a process’s isolation/modularity.

The first type of IPC is called Message-Passing. The OS opens a channel of communication for the two processes (like a shared buffer). Each process can write to and receive from the shared channel to communicate. The OS acts as a mediator and provides a user interface. The downside is that because the OS is involved, there is a hit to performance.

The second IPC method is called Shared Memory. Here, the OS establishes a shared channel and maps it into each of the process’s address spaces (memory). This makes communication fast, but the OS does not mediate, so it is up to each process to create its own read/write methods.

Threads

Before threading, concurrent programming occurred via multi-process applications. That is, the application makes a fork or exec call to launch a child process. Every process needs to be isolated and endowed with its resources by the OS. Processes are expensive. And it was common for applications to run copies of themselves. These copies had the same variables, code, and execution flow. With multi-threading, multi-process applications could shift to a new paradigm of concurrency.

Sun OS was one of the first operating systems built around multi-threading and multi-CPU usage. Its design continues to remain relevant and is what many modern practices can be traced back to.

You can think of a thread as a miniature process within a process. But unlike processes, threads share their virtual memory space with the process. Each thread is a context of execution. Threads can access common resources in a process. However, threads need to track their own:

- Program counter

- CPU register state

- Stack Pointer

You may already be seeing a similarity with process control blocks. If you did, good catch! Threads track their needed information by taking from the overall PCB into their data structure.

Threads are super useful for several reasons. First, they enable parallelization (multi-tasking). First, Threads divide tasks to work on a problem concurrently. Second, threads enable specialization. Recall that part of the issue with context-switching was the cache going cold. In multi-threading, this issue is less severe because threads are likely to be using similar resources. So, switching between threads is less likely to result in a cold cache.

Multi-threading generally trumps the multi-processes paradigm because a multi-threading application will have lower resource overhead, easier synchronization, and cheaper context switching.

Are threads useful on single CPU machines too? Yes! Because threads share memory, context switching is cheaper. Furthermore, if one threads blocks by doing an expensive operation, we can hide the application’s latency by switching to another thread! Switching threads is inherently cheaper than switching processes.

Thread lifetime

Threads creation is done through a parent thread (you can think of a process as a single-threaded application). The parent initializes a child thread with a function (depending on the library).

where should the thread begin its point of execution?

The child thread will initialize with a data structure that represents the new state of execution. The child thread goes ahead and executes concurrently with the parent thread. Generally, the child thread will exit first.

When the child thread finishes its work, it may go ahead and return some result. An easy way for the parent thread to get those results is to use a join call. The join function will result in the parent thread blocking (waiting) for the child thread to complete. Once completed, the result associated with the child thread is returned to the parent via the join.

If there is only one child thread and one parent thread, and they do not use the same resources concurrently, then this is it! We have a concurrent program. However, an application with shared a resource (e.g., an array that all the threads want to access, etc.) and concurrent access of that resource, needs to consider synchronization constructs.

Synchronization and Parallelization

Synchronization is a way of coordinating multiple points of execution. Synchronization must guarantee the correctness of a program. There exists a multitude of synchronization constructs, but today we will only discuss mutexes and conditions.

Mutexes (locks)

In parallel programming, there is no guarantee of sequentiality. For example, if we told one thread to write a document, and another to read it, the reading thread will likely read incomplete data. Locks (mutexes) are a way of guaranteeing sequential, exclusive access to a shared resource. A resource that is locked is only accessible to that thread. All other threads are placed in a line to wait for their turn.

What happens to another thread that tries to access a locked resource? You can think of a mutex as a lock with some handy features. It tracks if it is locked, who the “owner” of the lock is, and any threads that tried to access the lock while it was locked. Threads that encountered a locked mutex are put to sleep in a queue. When the lock is released (unlocked), the mutex will wake up the waiting thread on its queue, where it can go ahead and try to obtain the lock again. Neat!

Mutexes make managing access easy. They are cheap to initialize and guarantee exclusive access to a resource. Exclusivity essentially makes the region of code (a critical section) protected by the mutex single-threaded. Code protected by a mutex should be small, fast, and only have to do with accessing/modifying a shared resource (e.g., a data structure, shared resource, etc.). Don’t forget every lock should have a corresponding unlock!

Check out your language’s multi-threading library for interface specifics. C has pthreads, Java has Thread,…

What happens if you have just left your friends home with their car keys and your friend has your house keys? In programming, we call this a deadlock situation. Mutexes are powerful. Powerful enough to make a program get stuck. Avoid allowing a thread to take a lock and later have to take another lock. This makes your code vulnerable to having a thread waiting for another thread to give up its lock, while that thread is waiting for the first thread to give up theirs!

Condition variables

Sometimes you only want threads to run only when a condition occurs, or another thread tells it. The condition construct signals when threads should start working. You will always want to associate a condition variable with a mutex.

First, the thread has to hold the mutex. Then, we check if a condition is met (e.g., while, if). If this condition is not met, we tell the thread to wait using the mutex and condition. The thread then unlocks the mutex and is put to sleep. When the condition variable is signaled, sleeping threads can be woken to go ahead and work. There are two signals:

- signal(condition), wake-up a single sleeping thread associated with the condition

- broadcast(condition), wake-up all sleeping threads associated with the mutex

It is often preferable to use a while loop to check on the condition because a while loop will provide several assurances. First, the while loop can deal with multiple threads. Second, when we use signal, we can’t guarantee the order to which waking threads will access the mutex. Finally, the while loop safeguards cases where the condition can change.

Something to watch out for with condition variables is waking a thread, just to have it go back to sleep on the wait. This wake-immediately-sleep cycle is called a spurious wake-up. Spurious wake-ups are a waste of CPU cycles and can usually be solved by reordering mutex locks and unlocks.